Human rights apply to all of us, simply because we are human beings and regardless of the ethnicity, gender, religion, etc. (check out this overview clip). People sometimes argue that human rights are a Western concept and therefore cannot be transferred to other countries. However, they are part of international law and national governments have committed themselves to observing them, many of them have also ratified respective human rights laws. The history of human rights goes back to the French revolution and the era of constitutionalism (starting from the 18th century in the USA and in Europe). Another important date was the foundation of the International Labour Organisation in 1919 and the definition of standards and fundamental principles and rights at work. The first international agreement was the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, followed by the International Convention of Civil/Political Rights and the International Convention of Economic/Social and Cultural Rights in 1966.

Human rights are divided into three dimensions:

- Civil & Political Rights, e. g. right to freedom of belief and religion or the right to participate in government and in free elections;

- Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, e. g. right to desirable work, right to adequate living standard or right to education;

- Collective Rights, e.g. right to peace or right to a safe, healthy and ecologically-balanced environment.

In the 1990ies a paradigm shift from a growth-centred agenda to a more human-centred understanding of development could be observed. The Rights-Based Approach (RBA) was adopted by UN organisations and it is explicitly shaped by human rights and human rights principles. The RBA and its practical application in the context of small NGOs and community-based organisations was then presented by Kalkidan Negash Obse, a former APPEAR scholarship holder. He stressed that human rights are not privileges, mere aspirations or wishful thinking but rather justified claims protected by law, that lead to correlative duties and obligations for governments. In his talk Kalkidan compared the charity, the needs and the rights-based approaches. The RBA framework integrates the principles of the international human rights system into the plans and processes of development. Therefore, it represents a transition away from a charity or welfare model of development to an approach where individuals are aware of their rights. Stakeholders such as governments are seen as duty-bearers. Structural causes of poverty and inequality as well as their manifestations are in the focus of this approach.

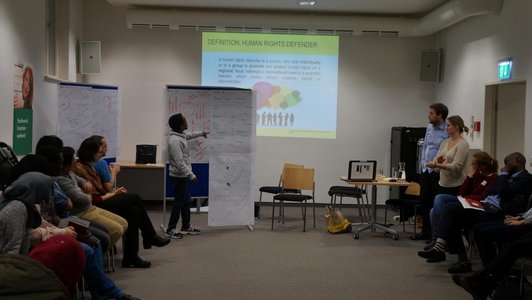

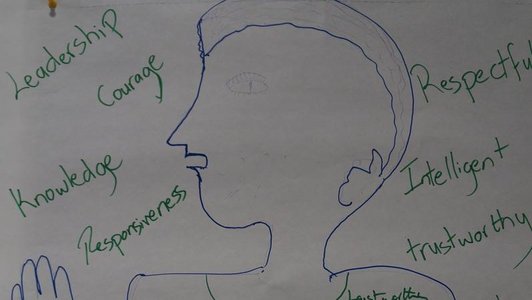

Following the theoretical inputs we started the interactive group work. The first question was what a human rights defender looks like. With the help of creative paintings the participants discussed different attributes – courage, open-mindedness, persistence, and respect – attributes that are needed to uphold human rights (watch the video “What does it mean to be brave?”). A more standardized definition of a human rights defender was given by the colleagues from Amnesty International: “a person, who acts individually or in a group to promote and protect human rights on a regional, local, national or international level in a peaceful manner, which means without violence, hatred or discrimination.”

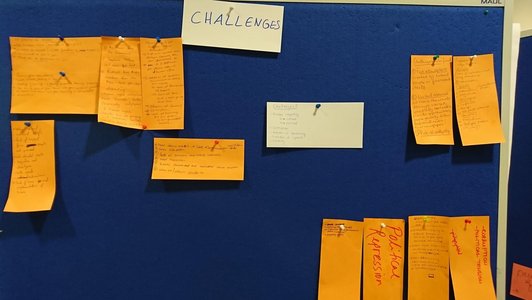

Students and researchers from 15 countries participated in the workshop and gave insights in the respective human rights situation of their respective country. Many examples about challenges concerning human rights all over the world were given. Theoretically, the state is responsible to protect human rights. However, in many countries freedom of speech is limited and violations of human rights are directly committed by governments. Critical persons fear sanctions, prison or threats against their families. Nationalism and prejudices between ethnical groups or religions are the cause of conflicts.

In the last part of the workshop the participants discussed how to become an active agent for human rights. Education, awareness raising and learning from other people or history were mentioned as possibilities. One student raised the issue of current slave trade incidents in Libya and asked what can be done. It is easy to get overwhelmed by this kind of atrocities that take place all over the world. Therefore, it was agreed to start with human rights issues that are closest to our homes. We can use our voice to criticise human rights violations publicly, to start conversations with friends, colleagues or even strangers, to join groups, protests and campaigns. In our own life we have to include different people and speak up against discrimination. Our governments must be held responsible and finally we should always focus on the true cause of problems and understand the broader context.

Becoming an active agent for human rights it is not an easy task and requires courage. Nevertheless, sharing experiences and best practice examples in a group of like-minded people inspires and strengthens the confidence to stand-up for human rights.

Organisers

This workshop was jointly organised with Amnesty International Austria and the APPEAR programme. In 2017 the APPEAR office organised different human rights events; see the recap of the Film Days in Vienna or the workshop at the University of Graz.

The Amnesty Academy strengthens the human rights movement through action oriented education. It offers free human rights online courses in English, Spanish, French and Arabic, in order to train a new generation of human rights defenders.

Speakers

Kalkidan Negash Obse received his PhD degree in International Law from the University of Graz in Austria. He has been a doctoral fellow at The Hague Academy of International Law in the Netherlands. Currently, he is the President of Dilla University in Southern Ethiopia, where before he has been working as Academic Vice-President. Furthermore, he was Assistant Professor of African Union law and human rights at Addis Ababa University (AAU), where he had previously served as Director of the University’s Center for Human Rights. Dr. Obse has several publications on African Union law and human rights.

Jens Kessler studied English and Geography at the University of Augsburg and completed a master’s degree in education. After teaching at different schools he studied international development at the University of Vienna. He worked in a school project in Uganda with former child soldiers. Since 2015 he is the coordinator of the adult education programme at Amnesty International Austria.

Julia Streimelweger is an activist for human rights education since 2015 and studies political science at the University of Vienna. The focus in her studies is on women rights, Gender equality policy in international relations and the European Union. Currently, she is writing her Master thesis on problems of social reproduction for local politicians with a focus on gender specific challenges.